One of the most common tactics is to claim that the Church, or a member of the magisterium, is wrongly intruding into the concerns of the state or offering a political opinion. Such dissenters overlook seem to forget that totalitarian dictatorships made the same complaint about the Catholic Church. Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and many other regimes have bitterly complained when the Church condemned the evils of their regimes. It becomes especially bizarre when those who hold positions that the Church speaks out against are themselves Catholic. Those individuals come across like King Ahab speaking bitterly against the prophet Micaiah:

Jehoshaphat said, “Is there no other prophet of the Lord here we might consult?” The king of Israel answered, “There is one other man through whom we might consult the Lord; but I hate him because he prophesies not good but evil about me. He is Micaiah, son of Imlah.” (1 Kings 22:7–8)

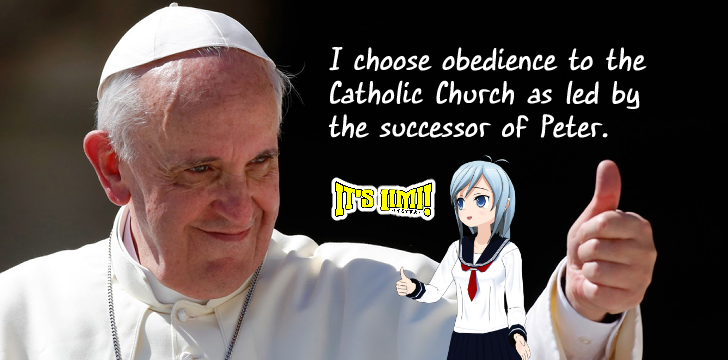

Common sense says that, when one who speaks with God’s authority speaks against the position a person holds, the person who recognizes that authority in general is a fool if they reject it when directed at him or her. We might laugh at Ahab’s foolishness in refusing to listen, but if we start saying in response to a bishop acting in communion with the Pope, “the Church should be silent, and stick to what they know,” we’re behaving like Ahab did.

Another application of this misrepresentation is when Catholics draw a line in the sand where the Church stays on one side and the state stays on the other. The problem is, this line is arbitrary and does not resemble what the Church actually believes. The Church does in fact have something to say when the state behaves in an unjust way, persecuting those who do right and permitting evils. This is because the Church has a role in speaking out to ensure justice when those who govern violate what is right. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church points out:

1930 Respect for the human person entails respect for the rights that flow from his dignity as a creature. These rights are prior to society and must be recognized by it. They are the basis of the moral legitimacy of every authority: by flouting them, or refusing to recognize them in its positive legislation, a society undermines its own moral legitimacy. If it does not respect them, authority can rely only on force or violence to obtain obedience from its subjects. It is the Church’s role to remind men of good will of these rights and to distinguish them from unwarranted or false claims.

A state only has legitimacy if it acts in a way that is just. When the state acts unjustly, the Church must speak out to warn those who govern about the danger to their souls and to the legitimacy of the state, as well as to warn Catholics who live within not to be swept up into supporting the evil. So, when the dissenters side with the rule of government or ideology of a politician in opposition to the teaching of the Church, they are choosing to reject the Church. And, since Catholics should know that the Church teaches with God’s authority (Matthew 16:19, 18:18), then to reject the authority of the Church is to reject God (Luke 10:16).

To get around that, dissenters like to point to sin in the Church and try to claim that grevious evils by some means the guilt of the whole. And, if the whole is guilty (they argue), then the Church cannot teach with authority until those in authority eliminate those evils. Some go so far as to say that the existence of evil removes the authority to teach. It’s a sort of neo-Donatism that pops up in the Church from time to time. Those who promote it will point to evils that exist, and say that the Pope and bishops have lost their authority (something they assume but do not prove). From there (through a non sequitur) they argue that what they teach is right. When the Church rejects their erroneous views, they point to the evil and rejects the authority of the Church. (Martin Luther and John Calvin were especially notorious with this tactic).

The problem is, even though Scripture has a lot to say about what will happen to faithless shepherds, they don’t say that sinful behavior removes authority. Aaron created a golden calf. He did not lose his office for his sin. Peter denied Jesus three times. He did not lose his office. Indeed, Our Lord pointed out (Matthew 23:2-3) that there was a difference between authority and personal behavior. Those who teach with authority must be heeded, but we may not use their bad behavior to justify ours.

Yet another tactic is to argue that X is a worse evil than Y, therefore the Church should not focus on Y while X exists. This is a red herring fallacy, aimed at discrediting those in the Church speaking against Y. Yes, some sins are worse than others. But, if X is less common in the Church in a nation, while people routinely commit Y, it makes sense that the Church would remind the faithful of the fact that Y is evil, lest they go to hell for committing it. As Ezekiel warned through prophecy:

You, son of man—I have appointed you as a sentinel for the house of Israel; when you hear a word from my mouth, you must warn them for me. When I say to the wicked, “You wicked, you must die,” and you do not speak up to warn the wicked about their ways, they shall die in their sins, but I will hold you responsible for their blood. If, however, you warn the wicked to turn from their ways, but they do not, then they shall die in their sins, but you shall save your life. (Ezekiel 33:7-9)

When the Church calls us out for supporting Y, we often say “the Church should speak out on X instead,” overlooking the fact that we forget their speaking out against X because we resent being called out over Y. But we should be grateful that the Church, as watchman, does not remain silent when we are the ones in danger of hell.

When we’re tempted to balk at the teaching of the Church, we should consider these ways in which we try to evade the religious submission of intellect and will. The Church teaches with the authority of Christ, and we should be very wary around arguments denying that authority.

Yes, there will be those in the Church who do fall into error when they try to teach in opposition to the Pope. But we trust that God will not permit His Church under the headship of the Pope to teach binding error. Yes, a teaching of the ordinary magisterium is changeable. But that means it can be refined, not that it was heresy before. If we accuse the Church, when she teaches, of teaching error, we are acting like Ahab who dared to be angry when a prophet warned him of his destruction.