One of the popular citations used against Pope Francis (or Vatican II) comes from St. Vincent of Lerins, on defining what is Catholic:

Moreover, in the Catholic Church itself, all possible care must be taken, that we hold that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, by all. For that is truly and in the strictest sense Catholic,

which, as the name itself and the reason of the thing declare, comprehends all universally. This rule we shall observe if we follow universality, antiquity, consent. We shall follow universality if we confess that one faith to be true, which the whole Church throughout the world confesses; antiquity, if we in no wise depart from those interpretations which it is manifest were notoriously held by our holy ancestors and fathers; consent, in like manner, if in antiquity itself we adhere to the consentient definitions and determinations of all, or at the least of almost all priests and doctors.

The definition is true in itself. The Catholic Faith is consistently taught from generation to generation. No faithful Catholic would deny it. The witness of the Apostles and their successors is constant, and someone who taught otherwise (St. Vincent was writing against the novelties of Donatists and Arians) was identified as heretical when they contradicted this ancient Faith.

The problem with the modern citation of this ancient writing (written AD 434) is it overlooks the legitimate development of doctrine. As St. John Paul II wrote in

Ecclesia Dei, #4:

The root of this schismatic act can be discerned in an incomplete and contradictory notion of Tradition. Incomplete, because it does not take sufficiently into account the living character of Tradition, which, as the Second Vatican Council clearly taught, "comes from the apostles and progresses in the Church with the help of the Holy Spirit. There is a growth in insight into the realities and words that are being passed on. This comes about in various ways. It comes through the contemplation and study of believers who ponder these things in their hearts. It comes from the intimate sense of spiritual realities which they experience. And it comes from the preaching of those who have received, along with their right of succession in the episcopate, the sure charism of truth".(5)

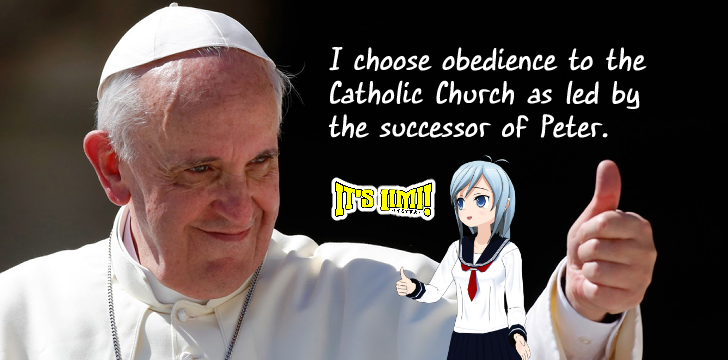

But especially contradictory is a notion of Tradition which opposes the universal Magisterium of the Church possessed by the Bishop of Rome and the Body of Bishops. It is impossible to remain faithful to the Tradition while breaking the ecclesial bond with him to whom, in the person of the Apostle Peter, Christ himself entrusted the ministry of unity in his Church.(6)

The problem with the current attacks on the legitimate development of the Church teaching is that the critics use St. Vincent of Lerins falsely. They look to what the Church Fathers and Medieval Theologians said about a topic and compare it with what the Church says today. But they confuse what the Church Fathers wrote with what they think the Church Fathers mean, not understanding the context of the writing.

Here’s an example. I have encountered some Feeneyite leaning Catholics who argued that non-Catholics necessarily go to Hell because Pope Boniface VIII wrote, in the Bull

Unam Sanctam: “

Furthermore, we declare, we proclaim, we define that it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff.” Since non-Catholics aren’t subject to the Pope, these Catholics argue that non-Catholics cannot be saved.

The problem is, the context of Unam Sanctam was not written about those outside of the Church. It was about King Philip the Fair, of France, demanding that the French clergy put obedience to him before obedience to the Pope. Pope Boniface was teaching that no secular ruler could claim a higher authority over the Church. That doesn’t mean that one can refuse obedience to the Pope. It means that these Catholics were misapplying a teaching in a way that was never intended. Whatever “contradiction” they think they saw with later teaching, it was never intended by the original teaching.

This is a growing problem with the Church today. Faithful Catholics are not wrong to study the writing of the Saints and Doctors of the Church. But if they rely on their own “plain sense” reading without considering subsequent development on how it is applied, they risk deceiving themselves into making themselves into what I call a “ME-gesterium,” where they pass judgment on Church teaching on the grounds that what the Church teaches doesn’t match with their personal interpretation.

I think Blessed John Cardinal Newman’s words about converts who left the Catholic Church again applies to this mindset as well:

I will take one more instance. A man is converted to the Catholic Church from his admiration of its religious system, and his disgust with Protestantism. That admiration remains; but, after a time, he leaves his new faith, perhaps returns to his old. The reason, if we may conjecture, may sometimes be this: he has never believed in the Church’s infallibility; in her doctrinal truth he has believed, but in her infallibility, no. He was asked, before he was received, whether he held all that the Church taught, he replied he did; but he understood the question to mean, whether he held those particular doctrines “which at that time the Church in matter of fact formally taught,” whereas it really meant “whatever the Church then or at any future time should teach.” Thus, he never had the indispensable and elementary faith of a Catholic, and was simply no subject for reception into the fold of the Church. This being the case, when the Immaculate Conception is defined, he feels that it is something more than he bargained for when he became a Catholic, and accordingly he gives up his religious profession. The world will say that he has lost his certitude of the divinity of the Catholic Faith, but he never had it.

—An Essay in Aid to a Grammar of Assent, page 240

In the case of the “ME-gesterium” Catholic, he or she probably remains in the Church, but considers any future development of the Faith to be “error” that needs to be overturned.

The Church is infallible in teaching ex cathedra in a special way. But the protection of the Church also falls on the Ordinary Magisterium of the Church—which is the normal way the Church teaches [§]. As Ven. Pius XII put it (Humani Generis #20):

20. Nor must it be thought that what is expounded in Encyclical Letters does not of itself demand consent, since in writing such Letters the Popes do not exercise the supreme power of their Teaching Authority. For these matters are taught with the ordinary teaching authority, of which it is true to say: "He who heareth you, heareth me";[3] and generally what is expounded and inculcated in Encyclical Letters already for other reasons appertains to Catholic doctrine. But if the Supreme Pontiffs in their official documents purposely pass judgment on a matter up to that time under dispute, it is obvious that that matter, according to the mind and will of the Pontiffs, cannot be any longer considered a question open to discussion among theologians.

Likewise, Lumen Gentium 25 tells us:

25. Among the principal duties of bishops the preaching of the Gospel occupies an eminent place. For bishops are preachers of the faith, who lead new disciples to Christ, and they are authentic teachers, that is, teachers endowed with the authority of Christ, who preach to the people committed to them the faith they must believe and put into practice, and by the light of the Holy Spirit illustrate that faith. They bring forth from the treasury of Revelation new things and old, making it bear fruit and vigilantly warding off any errors that threaten their flock. Bishops, teaching in communion with the Roman Pontiff, are to be respected by all as witnesses to divine and Catholic truth. In matters of faith and morals, the bishops speak in the name of Christ and the faithful are to accept their teaching and adhere to it with a religious assent. This religious submission of mind and will must be shown in a special way to the authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff, even when he is not speaking ex cathedra; that is, it must be shown in such a way that his supreme magisterium is acknowledged with reverence, the judgments made by him are sincerely adhered to, according to his manifest mind and will. His mind and will in the matter may be known either from the character of the documents, from his frequent repetition of the same doctrine, or from his manner of speaking.

This is confirmed in Canon 752:

can. 752† Although not an assent of faith, a religious submission of the intellect and will must be given to a doctrine which the Supreme Pontiff or the college of bishops declares concerning faith or morals when they exercise the authentic magisterium, even if they do not intend to proclaim it by definitive act; therefore, the Christian faithful are to take care to avoid those things which do not agree with it.

Notice that the Church consistently teaches that even the ordinary magisterium is binding on the faithful. This undercuts the common claim that whatever is of the ordinary magisterium is merely opinion that is liable to error.

The “ME-gesterium” has a dangerous pitfall: it assumes that the individual can clearly understand the past writing of the Church but the Pope and bishops in communion with him do not. It assumes that the individual cannot err but the Pope can if his teaching goes against their understanding. It assumes that every teacher past and present speaks and reasons as a 21st century American so a grasp of history (ecclesiastical and secular) and culture is not needed to understand the full import of past teachings in the context of today.

Ultimately, the danger of the ME-gesterium is pride. The individual thinks they cannot err, but the Church can. In claiming to defend the Church from “heresy,” they take the first step towards it: denying the authority of the Church to determine the proper interpretation of the timeless teachings to meet the moral concerns of today.

If we want to be faithful Catholics, let us recognize that God protects His Church. Not all Popes or bishops have been saints. Some were bad men. But God protected the Church from error in the worst of times. That protection exists now and until the consummation of the world (Matthew 28:20). If we do not believe that, we should recognize it as a warning sign that our own faith is in danger.

—————————————

[§] Most ex cathedra teachings were made to combat heresies which refused to obey the Ordinary Magisterium.